The street lieutenant fidgeting in a Ciudad Juárez pizza parlor deals drugs for Barrio Azteca, a gang that emerged from Texas prisons in the 1980s to control a chunk of illegal shipments from Mexico into the U.S. Southwest. Think No Country for Old Men—secret nighttime drops, murders, and a lucrative sideline in human trafficking and prostitution. Meeting with a reporter while his heavyset boss circles the block, the Juárez dealer is preoccupied with his hottest new product: handcrafted American-made pot.

He marvels at one medical marijuana operation he visited in Arizona. “There are tanks with a system that at a certain hour releases oxygen, water, and light like clockwork,” says the man, who asked that his name not be used for fear of arrest or reprisals from other gang members. Connoisseurs in Juárez are noticing, he says; they’re starting to demand Purple Haze or Kush from American dispensaries. Gang members bring the quality stuff back from the U.S. The prices are higher—about 200 pesos per gram, compared with 50 pesos for his usual product—but then so is the quality. “There’s much more novelty, more variety,” he says.

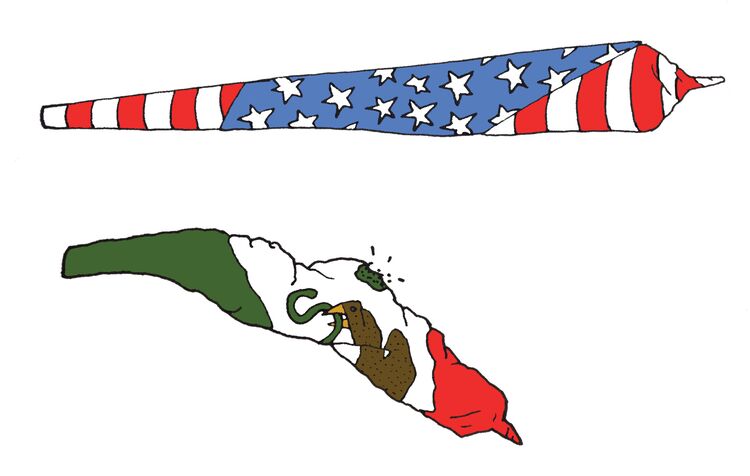

With marijuana now permitted in some form in 23 U.S. states, the usual flow of pot from south to north has slowed and, to a growing degree, reversed. This was never imagined as a benefit of Nafta. Now, the expanding U.S. pot industry is transforming the drug distribution patterns of the notorious cartels—forcing them to deal more exclusively in heroin, for example—and leading to both cultural and economic change in Mexico’s own consumption of marijuana. Two opportunities may arise: a business boom for legal pot producers in the U.S. and the chance to concentrate the drug war on far more deadly substances.

The effects are being felt in Sinaloa, long the heart of Mexican pot production. Farmers there are ripping out marijuana planted on hillsides. “In our town, it’s dropped because it’s no longer a profitable business,” says Mario Valenzuela, mayor of Badiraguato, the hometown of infamous drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, who was arrested in 2014. Over the last two years, participation in a program that subsidizes farmers who plant crops like tomatoes or green beans instead of marijuana has increased 30 percent, Valenzuela says. He attributes the increase to the surge in U.S. production since legalization.

In the past, only a sixth of cannabis consumed in the U.S. was grown within the 50 states; today that’s up to at least one-third, according to the United Nations. Pot from Colorado and California has started to displace the low-grade stuff that’s long flowed in by truck, tunnel, human mule, and boat from Mexico. Marijuana seizures by U.S. Customs and Border Protection at California border crossings totaled 132,075 pounds in fiscal 2014, half of the amount five years earlier.

Colorado weed carries such cachet in both the U.S. and Mexico that entrepreneurs like Shawn Lucas, founder of a Denver grow-equipment supplier called Dutch Hort, say it could one day be a global brand. The state’s burgeoning export prowess has already irked Nebraska and Oklahoma, where marijuana is still illegal. They claim a rise in crime related to pot from their neighbor and, in December, petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to shut down Colorado’s pot production. In Mexico City, young men mingling at an outdoor market and hawking mota—or pot—namecheck brands popular north of the border. By 2020, if marijuana were fully legalized, American sales might reach $35 billion, says Matt Karnes, a former media analyst at First Union Securities who now runs New York-based cannabis researcher GreenWave Advisors. That’s not much less than the $38.5 billion Americans spent at pizza restaurants last year.

Lucas, 37, is typical of pot’s shift to the mainstream. He started growing weed at 16 with seeds ordered from Canada. He opened shops selling nutrients, always taking care to speak in code with customers. At the time, only a few states allowed medical marijuana. “If you even hinted at the word ‘cannabis’ or ‘weed,’ I had to kick you out,” Lucas says. “I wasn’t going to go to jail for you.” He spent a few years in Shenzhen, China, developing contacts with manufacturers of the high-intensity-discharge lamps used by marijuana growers. Now, one of his Colorado clients has 6,000 lights, each retailing for $600. “I never thought I’d see that,” Lucas says. “This has been my entire adult career.”

Mexico has been wracked for years by the fallout of a bloody drug war, stoked by prohibitionist sentiment in the U.S. It began one Sunday in 1969, when President Richard Nixon ordered a surprise inspection of every vehicle crossing into the U.S. Now the border, made manifest by 650 miles of fencing, teems with Predator drones, ground sensors, and surveillance cameras. Turf battles made Ciudad Juárez one of the most violent cities in the world earlier in this decade, with 1,900 murders in 2011.

Mexico decriminalized possession of 5 grams or less of marijuana in 2009. A bill introduced last year would allow pot dispensaries like those in many U.S. states. “Why should we be killing each other over marijuana?” asks Mexico City lawmaker Vidal Llerenas, a backer of legalization. “We have a war here to prevent it from going to a country where it’s already legal.”

While the bill has languished so far, momentum will grow if California approves recreational pot sales in a measure likely to appear on ballots in November 2016. “If California legalizes, you can’t politically sustain prohibition in Mexico,” says Jorge Javier Romero, president of a drug policy organization in Mexico City known as CUPIHD. Some 64 percent of Mexicans support allowing marijuana for medicinal use, according to an August 2013 survey by pollster Parametria—an eye-opener for a country that’s also one of the world’s most Catholic.

Some aren’t waiting for the state’s blessing. Carlos Zamudio, 37, helped open La Semilla Growshop in Mexico City in February, selling lamps and nutrients, often imported from the U.S. or Canada. One model on his floor, the XXXtreme 6 grow light, is made by Hydrofarm, a hydroponics supplier in Petaluma, Calif., near the state’s famed Emerald Triangle of pot farms. Zamudio says his grow shop is one of at least four in Mexico City. “The market is opening,” he says.

Pepe Pallán is trying to build a network of patients and doctors, even though medical marijuana isn’t officially allowed yet. A fan of the U.S. television series Weeds, about a drug-dealing single mom, Pallán, 38, hopes to go to California to attend Oakland’s Oaksterdam University, which calls itself the first “marijuana college.” Pallán tries to connect clients in Mexico City with doctors who agree to supervise treatment. He gets the pot from a grower who uses organic methods and avoids the cartels. “I’m not going into business with those guys,” he says.

Those guys are not going out of business, unfortunately. Mexico’s drug lords may have lost some profits because of U.S. legalization, but they’ve made adjustments. They’ve likely replaced volume lost from their pot trade with higher sales of heroin and methamphetamines, says Adam Isacson, a senior associate at the Washington Office on Latin America, a policy group. Some of the farmers abandoning weed are turning to cultivating poppies for heroin, helping fuel a near tripling in U.S. overdose deaths from the drug since 2010. Half of the heroin in the U.S. now comes from Mexico, up from 14 percent in 2009, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration says.

The drug war isn’t over. Yet there has been an historic change at the border. The fight can now focus on heroin and other deadly substances. The toll of the war on marijuana has been huge in terms of security and lives. Decades of prohibition never slowed the flow of pot from Mexico; legalization did. The choice is now who controls that flow: an unnamed dealer in Juárez or a legalized cross-border industry.

>> source